Executive summary

I crossed the finish line of the 500-mile Northern New Mexico Loop (NNML) on September 6, 2025, completing the self-supported adventure in 12 days, 16 hours, and 17 minutes. This marks my second major undertaking in the Land of Enchantment, following my completion of the 300-mile Monumental Loop back in 2021. Having spent several years living and working in New Mexico, this journey felt like more than just another endurance challenge: it was a return to a place that I love, making every mile a bit of homecoming.

The Northern New Mexico Loop (NNML)

The Northern New Mexico Loop (NNML) is a 500-mile hidden gem in the Land of Enchantment. The well-established route is the brainchild of Brett Tucker & Melissa Spencer (creators of the Grand Enchantment Trail and the brand new 1,1000-mile Oregon’s Sea-Snake Route) and offers one of the Southwest’s most diverse and challenging long-distance hiking experiences. The loop format is particularly appealing, allowing hikers to start and end in the same accessible location while experiencing the full diversity of northern New Mexico’s landscapes.

Starting and ending at the Santa Fe Plaza, the loop winds through many of the most beloved hiking trails in northern New Mexico. Hikers are taken through high desert pine forests and mountains over 10,000 feet in elevation, through deep canyons and arid farmland, and over stunning mesas. The route passes through iconic locations including the Jemez, Ghost Ranch, near Chama, Questa, Taos Ski Valley, Red River, Eagle Nest, Angel Fire, Sipapu, and the Pecos Wilderness, plus Bandelier National Monument with its ancestral pueblo dwellings and rock images. The cultural richness is unmatched, with arguably the best food available for any long hike available in Santa Fe, along with the city’s rich history and vibrant art scene. The Rio Grande features prominently in the grand scheme of the hike, and the route offers a very respectable number of trail miles rather than being primarily road walking like some alternative routes.

- Trails: 345 mi (66%)

- Dirt roads: 128 mi (24%)

- Cross-country: 25 mi (5%)

- Paved roads: 25 mi (5%)

- S1 – Santa Fe to La Cueva: 78.1mi

- S2 – La Cueva to Ghost Ranch: 76mi

- S3 – Ghost Ranch to Chama: 78mi

- S4 – Chama to Questa: 60mi

- S5 – Questa to Red River: 33.3mi

- S6 – Red River to San Cristobal: 27mi

- S7 – San Cristobal to Taos: 39mi

- S8 – Taos to Santa Fe: 91.8mi

- TOTAL: 483.2mi

My own total distance added up to 495.95mi. I did the route counter-clockwise, i.e., I started with section 8 in Santa Fe and first went to Taos.

As you can see in this interactive map, the route has several alternatives. For my FKT, I followed main route (marked in blue).

Day 1 (Aug 25)

The Santa Fe Plaza was unusually empty when I arrived at 3:50am on August 25, 2025. My goal was to start precisely at 4am—any big adventure demands this kind of ritualistic precision. The pre-dawn silence felt appropriate for the journey ahead: extraordinary landscapes, relentless monsoon weather, dangerous river crossings, and the kind of solitude that makes you question everything—including your sanity.

My pack felt heavy. I was carrying food for roughly 2.5 days to cover the first 90-mile section to Taos, plus full overnight gear for potential below-freezing temperatures at elevation.

I cleared Santa Fe’s paved roads in darkness, my headlamp beam cutting through the crisp mountain air. Soon I was on the familiar Dale Bale trails, a network I’d ridden countless times on my mountain bike over 17 years ago when I lived here. Time has a way of collapsing in places like this—the singletrack felt exactly as I remembered it, despite the intervening decades.

The trails wound deeper into the foothills, eventually connecting to the Winsor Trail that I’d hiked many times en route to Santa Fe Baldy (12,632ft). There’s something profound about starting a major journey on familiar terrain—it provides confidence while simultaneously highlighting just how far into the unknown you’re about to venture.

As I climbed higher and waved goodbye to the last lights of Santa Fe, the Pecos Wilderness opened before me. This is New Mexico’s largest wilderness area at nearly 224,000 acres, a landscape of high alpine lakes, ancient forests, and peaks that reach above 13,000 feet.

In the early afternoon, somewhere along the remote high country trails, I encountered Aspen—the one and only NNML hiker I would meet during the entire loop. This speaks to both the route’s difficulty and its relative obscurity compared to more famous long-distance trails. Aspen had started the loop clockwise in spring but was forced to bail due to snow conditions. Rather than abandon the goal entirely, they’d returned to complete the route in several staged sections. We exchanged some trail intelligence: water source reliability, recent weather impacts, trail conditions ahead.

By late afternoon, the familiar afternoon thunderstorm pattern began developing. Towering cumulonimbus clouds built rapidly over the peaks, and I could hear the distant rumble of thunder echoing through the valleys. I’d hoped to push deep into the night on this first day, maximizing distance while energy levels were still high. But when the first fat raindrops started falling and I spotted a decent campsite among a cluster of mature pines, experience trumped ambition. I quickly established camp while everything was still dry. The decision proved wise. What started as light rain evolved into a violent thunderstorm that raged most of the night. I spent hours lying awake, periodically checking that my gear remained dry.

When my 3am alarm sounded, I felt far from rested. But the storm had passed, leaving behind that distinctive post-storm clarity in the mountain air.

Day 2 (Aug 26)

Everything was soaked when I packed up at 3am, despite my best efforts to keep gear dry. Welcome to monsoon season hiking! Nothing a waffle with mayonnaise couldn’t improve, at least temporarily.

August in New Mexico typically marks the height of monsoon season, and 2025 delivered in spectacular fashion. The North American Monsoon, which brings approximately 50% of the state’s annual precipitation between June and September, was operating in overdrive.

Weather forecasters had predicted “an active start to the monsoon season in July before slowing down in August.” This proved wildly inaccurate. Instead, the thunderstorms intensified through August, arriving daily and often multiple times per day. The monsoon’s diurnal cycle became the metronome of my daily routine: relatively calm mornings giving way to towering cumulonimbus clouds by early afternoon, followed by spectacular lightning displays, torrential downpours, and occasional hail. This meant I was essentially racing against time each day, trying to cover maximum ground before the afternoon storms hit with full force.

I quickly developed a rhythm around the weather pattern. Every day, I used the relatively calm period between late morning and early afternoon to: dry gear, eat, and take a nap. For the most part, this strategy worked. The relentless nature of the pattern was both predictable and exhausting. Every morning brought the same wet gear ritual. Every night brought the same careful site selection process, always with one eye on drainage patterns and lightning risk.

Day 3 (Aug 27)

I reached Ranchos de Taos (mile 92) before 9am. The timing was perfect for a proper breakfast at Mountain Monk Coffee, which sits directly on the NNML route.

What followed was, I believe, the NNML’s longest continuous road section—several miles of pavement and gravel roads leading to the first bridged Rio Grande crossing. Road walking on long-distance routes is necessary evil. The compensation came with the descent into the Rio Grande Gorge, a dramatic geological feature that cuts up to 800 feet deep through the high desert plateau. The approach views were spectacular, offering my first glimpse of the massive rift that would become a central character in this journey.

I crossed the Rio Grande at the Taos Junction bridge, getting my first close look at the river that would challenge me at the very end of the route. Here, the water looked and smelled questionable—a murky brown flow that bore little resemblance to the clear mountain streams I’d been drinking from.

Mid-day thunderstorms soaked me thoroughly during the climb out of the gorge on the western side, but the afternoon’s trail along the west rim made up for the discomfort. The West Rim trail that follows the gorge’s edge for miles offers spectacular views of the gorge and of the Rio Grande nearly 600 feet below. The challenge on this section was water scarcity. Despite spectacular views, the rim offered no reliable water sources.

I reached the famous Rio Grande Gorge bridge as darkness fell. This steel deck arch bridge, completed in 1965, spans the gorge at nearly 600 feet above the Rio Grande, making it the fifth-highest bridge in the United States. The bridge has appeared in numerous films and draws tourists year-round for its stunning views and dramatic architecture.

The section from the Rio Grande Gorge bridge to the John Dunn bridge departed from established trails and entered the realm of cross-country navigation. This stretch required constant attention to the GPS, terrain assessment, and route-finding. I completed this entire section in the dark. The navigation was intricate enough to keep me alert despite fatigue, but slow enough to be frustrating when I wanted to cover distance.

When I finally couldn’t move efficiently in the darkness, I established a cowboy camp beneath a magnificent old juniper tree. The clear sky and calm wind made this the first night I felt confident sleeping without shelter.

Day 4 (Aug 28)

I got up at 3am as usual and started my drop down into the Rio Grande Gorge. In the dark I crossed over the John Dunn bridge and started my way toward San Christobal. The stretch seemed to never end. I tried to enjoy the last views of the gorge, but was craving mountains again. San Christobal felt depressing at best. As in Ranchos de Taos, I was attacked by several dogs in San Christobal. These weren’t playful encounters. The dogs were aggressive and territorial and saw me as a threat. I began seriously regretting my decision not to carry pepper spray. Some encounters involved packs of multiple dogs, which felt genuinely dangerous. Unfortunately, New Mexico lacks a statewide leash law, and many rural property owners simply allow their dogs to roam freely around their homes.

People frequently ask about dangerous wildlife encounters—bears, mountain lions, rattlesnakes. The truth is that domestic dogs remain the most consistently problematic animals I encounter on runs.

I was looking forward to get into the Columbine-Hondo Wilderness and to leave the dog attacks behind. I filled up two bottles at the San Cristobal Creek, but later (= too late) realized that 1 liter was by no means enough for a long day on waterless ridges. I struggled unusually hard to make it up to Lobo Peak. I only realized at the summit that I was at 12,115 feet, about the same elevation as Mt. Adams. Perhaps it was the thin air, perhaps a lack of calories that I had accumulated over the last 3 days, or a combination thereof. But the struggle was real.

For the entire day, the trail stayed up high and relentlessly followed ridges and peaks and basins. In the late afternoon I concluded that I was getting seriously dehydrated. Thankfully I had saved an apple, which provided some relief to the painfully dry mouth. I was unable to eat something else. Only at dusk I finally reached Goose Lake and was able to fill up the bottles and the body with some more or less fresh water.

Sadly, I was unable to make it to Red River in time for some food. Red River is resort town in Taos County with lots of restaurants, stores, and lodging.

Day 5 (Aug 29)

I had about 5mi to go to Red River after waking up from another restless night. It was 5am when I reached the sleepy town. Nothing was open. I sat on a cold bench, studied my spreadsheets, and questioned my life choices while an unfriendly and cold wind made me even colder. I considered waiting two hours for the first breakfast places to open and also seriously I considered quitting. Warm food, hot coffee, and the possibility of a real bed for recovery. The temptation was substantial! Instead, I got up and followed my GPS track religiously, as I had done for the previous four days. Sometimes stubbornness masquerades as determination.

A private property on the Bitter Creek road required me to bushwhack around it, which probably cost me nearly an hour. That turned out to be only the beginning. I knew there would be another “impassible” section coming up on the Midnight trail #81, according to the information included in Brett’s mapset:

“Per reports from hikers, a portion of the main NNML route along Midnight Trail #81 in Section 5 (Questa to Red River section, approx MP 18.2 to 21.4) features hundreds of large blowdowns, rendering the trail essentially impassable following a severe winter wind storm. Because Midnight Trail is the only trail allowing for an easterly exit from Latir Peak Wilderness, the trail damage forces a larger detour, potentially missing this fantastic wilderness area altogether.Please refer to the following Caltopo map showing the suggested workaround/detour route: https://caltopo.com/m/0Q8GN. The route depicted offers a way to keep Latir on the itinerary by forming a “loop spur” of the Wilderness from the Cabresto Lake trailhead off FR 134 (Section 5 mile 7-8). Then, back at FR 134 after completing the loop, one can continue south on trails over Elephant Rock in order to reach the town of Red River sooner than otherwise and avoid additional roadwalking along FR 134. Distances from Questa to Red River along the original main route and new bypass approach are, conveniently, about the same (33-35 miles), so no changes need be made to food/time/distance for planning purposes. Please refer to the waypoints on the map for additional details and follow the large arrow icons to get a sense of the direction of travel when thru-hiking the NNML clockwise in the spring season.”

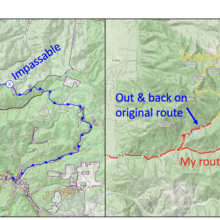

When I got to the Midnight trail, it quickly became obvious that this section needed to be detoured. The trail sign shown below speaks for itself. The tree nests were horrible in every aspect. I made it for about a mile, which took me forever. Then, not knowing how much more downfall was left to be dealt with, I activated my own detour plan.

In order to follow the main route more closely, I chose a slightly different way to detour the impassable section on the Midnight Trail #81:

- I pushed as far into the impassable section as possible before bailing out;

- I descended cross-country to reach Cabresto Canyon Road;

- I followed the road until rejoining the main route at the Cabresto lake turn-off;

To compensate for the ~6mi shorter walk on the road, I did an out-and-back on the original route (up to and past Cabresto lake). That also roughly compensated for the elevation gain. The total distance ended up being about 3 miles longer than the original route, more than compensating for the road detour.

Over the 500 miles, other minor deviations from the route were due to:

- Cross-country/off-trail sections

- Official trail re-routes

- New private property/trespassing situations

- Construction sites/closures

- Closures due to active logging

The included map shows an overlay of the original main route (yellow) and my own track (red). As one can see, the only significant deviation is the official Midnight trail #81 detour. The other deviations were so small that one can’t even see them on this overlay map.

Day 6 (Aug 30)

I pushed through Questa just after 4am, hoping the early hour would help me avoid the aggressive dogs that had become a consistent problem in rural New Mexico communities. This strategy failed spectacularly—I was attacked multiple times and had to use both trekking poles to keep hostile dogs at bay. Reaching the Las Vistas de Questa Trail outside town brought some relief.

Along the trail, I passed a fascinating memorial—a gravesite with three full, unopened cans of Coors beer. Someone had clearly loved their Coors! I wrestled with whether taking a can would constitute grave robbery, ultimately deciding to leave them untouched. But as the day progressed through increasingly hot and dry terrain, I regretted this decision multiple times. Nothing sounds better than a cold beer when you’re crossing miles of sagebrush desert under a blazing sun.

As daylight arrived, I reached the Rio Grande sheep (unbridged) crossing. I wasn’t sure what to expect, having heard varying reports about difficulty and danger. The crossing turned out to be remarkably straightforward.

After climbing out of the Rio Grande canyon, I entered the “sagebrush ocean”—miles and miles of high desert covered in sagebrush. The landscape has its own austere beauty, but it can be mentally challenging terrain because you feel like you are not making progress.

Water was sparse. I was able to refill bottles and even do laundry for the first time at two cattle troughs along the route. The first trough had flowing and relatively fresh water. The second trough’s water was questionable at best, but I wasn’t in a position to be selective.

Late in the afternoon, I began the ascent of San Antonio Mountain, unaware of what I was committing to. At dusk, I encountered a large camp of archery bear hunters who offered both warnings and information. “Be careful and turn on your headlamp,” they advised, “because there are lots of yahoos out here.” This wasn’t exactly comforting news. They also asked if I was going “over” the mountain, and I said yes without really understanding what this meant. San Antonio Mountain turned out to be just short of 11,000 feet high. “Getting over it” required a substantial climb in darkness, followed by a long descent to find a suitable campsite on the far side.

Day 7 (Aug 31)

The morning brought gorgeous forest and meadow travel. I was continually amazed by the scale and remoteness of these landscapes. The country felt endless and wild.

Somewhere along the Rio San Antonio canyon, I made a navigational misjudgment. Instead of climbing up to follow the canyon rim as the route intended, I stayed at the bottom and continued downstream. This seemed reasonable at first as there was some sort of trail, but it wasn’t. I wasted at least an hour bushwhacking through dense vegetation at the canyon bottom before realizing my error. Correcting the mistake required finding a passage through the rim rock to regain the proper route—a scramble that left me scratched and frustrated.

Later in the day, I was finally able to take my first real “bath” in a river since starting the journey. The water was considerably colder than I wanted, but the psychological and physical benefits were worth it. There’s something profoundly restorative about full-body immersion in natural water.

The day’s major challenge was the climb up to Brazos Ridge at over 10,000ft, where the NNML would finally intersect the Continental Divide Trail (CDT). I was looking forward to joining one of the country’s premier long-distance trails. Unfortunately, a terrible thunderstorm moved in while I was still high and exposed on the ridge. The combination of elevation, exposure, and electrical activity created a genuinely dangerous situation. Lightning at high elevation is one of the most serious hazards in mountain travel.

I made it down to the Lagunitos campground in a late evening thunderstorm and had to set up my tent in driving rain. Fortunately, the night wasn’t as wet as some previous storms, and I managed to get reasonable rest.

Day 8 (Sep 1 – Labor Day)

I had expected the Continental Divide Trail to bring encounters with other hikers. Instead, I saw exactly zero hikers on the entire NNML stretch that intersects with the CDT. This was surprising and somewhat disappointing. What the CDT lacked in human presence, it made up for in trail quality. The trail was well-maintained and marked. After days of route-finding and bushwhacking, walking on actual trail felt luxurious. The maintenance level suggested significant volunteer effort.

Being Labor Day weekend, I expected crowds everywhere. But reality again defied expectations. This speaks to the remoteness of this particular CDT section and the NNML’s route selection through truly wild country.

The day brought multiple storm cycles, some producing hail. At Hopewell Lake, I was able to wait out one particularly violent thunderstorm for about an hour. I used the shelter time productively: eating and napping.

The day ended with setting up camp above 10,000ft. The night was cold and windy but mostly dry, a welcome change from recent storm-battered camps.

Day 9 (Sep 2)

I secretly hoped to reach Ghost Ranch, a famous retreat center on the NNML route, in time for dinner, perhaps even to secure a room. But alas, the going was slower than anticipated, and by late afternoon I realized I wouldn’t arrive before 8pm. I later learned that dinner service ended at 6:30pm.

During the day, I had to lance a small blister. To demonstrate to my dentist that carrying some floss is always useful, I used floss for the procedure and discovered that the mint coating provided surprisingly soothing relief. The new La Sportiva Prodigio Max shoes had performed excellently throughout the journey so far. I’d purchased them just days before starting the NNML and had only completed one run in them before committing to 500 miles. This kind of gear gambling rarely works out, but it did this time

The descent to Ghost Ranch led through various canyons that showed clear evidence of recent severe flash flooding. Given the daily thunderstorms occurring throughout my journey, this made me somewhat nervous about potential water flow while I was in the drainages. Flash floods are a serious hazard in desert canyon systems, particularly during monsoon season. Water levels can rise from zero to deadly in minutes, and escape routes are often limited. I moved through these sections as quickly as possible while monitoring weather conditions upstream.

I reached Ghost Ranch after dark to find everything closed. I considered the ethics of using their pool for a quick rinse but decided it would likely get me in trouble.

I continued several more miles into the night until fatigue made efficient travel hard. With clear skies, I opted for another cowboy camp under the stars.

Day 10 (Sep 3)

At 1:30am, I woke to rain beginning to fall. Rather than wait for conditions to worsen and struggle with tent setup in the dark, I made the decision to pack quickly and start moving. I figured the “extra miles” completed in darkness would be appreciated later. The trail led up to the Chama River Canyon rim and followed it for several spectacular miles. After daylight arrived, the views proved to be among the rather impressive. The descent from the rim down to the Rio Chama was rather rocky and slow. I crossed the Rio Chama on a footbridge, grateful not to face another potentially dangerous ford.

Entering the Ojitos Canyon revealed the recent power of flash flooding in desert environments. The canyon had suffered catastrophic flood damage within the last day or two. Everything looked fresh and raw. Normal trail features were obliterated. Stream crossings had been completely rearranged. Vegetation was stripped away or buried under debris. Navigation markers were gone. I easily lost an hour trying to find a route through the destruction. This provided a sobering reminder of the forces I was traveling through during an active monsoon season. The same storms that had been soaking me nightly were creating genuine hazards throughout the region.

I made it into the San Pedro Parks wilderness on another substantial climb above 10,000ft. I established camp in windy conditions and spent another cold night at elevation.

Day 11 (Sep 4)

Somewhere in the San Pedro Parks wilderness, the NNML route departed from the CDT permanently. I had mixed feelings about this. The CDT had provided excellent trail quality and clear navigation, but it was also satisfying to return to the more adventurous character of the NNML. The route immediately entered a section with extensive downfall. I got thoroughly soaked in the process and found myself asking Pedro to release me from this particular ordeal. My wish was eventually granted, but it took several hours of slow, frustrating travel through the blowdown maze.

Late in the afternoon, I passed the turn-off to the San Antonio Hot Springs, a well-known geothermal area that attracts visitors year-round. The temptation was significant, but I made the practical decision to continue toward La Cueva instead. After 10 days without a proper shower, I felt too dirty and aromatic to inflict myself on other hot springs users.

Arriving in La Cueva after dark, I was certain that the store would be closed. But as I came around the final corner just before 8pm, I saw the beautiful sight of an “Open” sign still glowing brightly at the local store. I procured some treats, then continued several more miles into the night before finally stopping to rest.

Day 12 (Sep 5)

On day 12, I was finally starting to “smell the barn”—that psychological shift that occurs when the end of a major journey becomes tangible rather than theoretical. According to my original spreadsheet calculations, I was supposed to finish today and catch a flight home. Clearly, that wasn’t happening. As always, my spreadsheets proved overly optimistic about daily mileage capabilities under real conditions.

I was approaching the famous Valles Caldera. The Valles Caldera National Preserve encompasses 88,900 acres in the Jemez Mountains of north-central New Mexico. This landscape was created by a spectacular volcanic eruption approximately 1.2 million years ago that formed one of the largest calderas in the world. The caldera remains dormant but not extinct, still displaying signs of volcanic activity through hot springs and sulfuric acid fumaroles. The distinctive landscape features large grassland meadows (valles in Spanish) surrounded by rounded, forest-covered volcanic domes.

The views were indeed spectacular. The scale of the caldera is difficult to comprehend until you’re traveling across it. The grassland valleys stretch for miles, creating an almost African savanna appearance in the middle of the New Mexico mountains.

Later in the day, I entered Bandelier National Monument, an area I’d visited several times before. The monument preserves the ancestral Puebloan cliff dwellings and archaeological sites that represent over 10,000 years of human presence. Adolf Bandelier, the monument’s namesake, was a Swiss-American archaeologist born in Bern who particularly explored the indigenous cultures of the American Southwest, Mexico, and South America. He immigrated to the United States as a youth and dedicated his life to the new fields of archaeology and ethnology.

When I was still several miles from the Bandelier Visitor Center, torrential rains set in and continued for over three hours. I was soaked to the bones within minutes, and so was all my gear, despite supposedly “waterproof” compression sacks. The reality is that those packsacks are not waterproof against sustained submersion-level precipitation.

I began experiencing some signs of hypothermia, but made it to the visitor center, where I spent over an hour in a bathroom frantically trying to dry gear with the single hand dryer available. It was a desperately slow process, but it mostly worked. When the rain finally stopped, I managed to reach the Juniper campground. As soon as I had my tent set up, the rain resumed. I managed a few hours of sleep.

Day 13 (Sep 6)

Everything remained wet the next morning, including my sleeping bag and insulating layers. But this was hopefully the final day, so I wasn’t overly concerned about gear drying time. After some road walking that allowed me to dry shorts and shirt in the pre-dawn hours, I began the descent into the Rio Grande canyon for my final encounter with the river that had been a central character throughout this journey. I expected this unbridged crossing to be similar to my first one near Taos—straightforward and manageable. I was completely wrong. Even in darkness, I could hear the Rio Grande clearly—a loud, rushing sound that immediately indicated high water levels. This was bad news. The route follows the river for several miles, and as daylight revealed the full situation, I could see a wide, brown, turbulent mess. This crossing looked substantially more serious than I had anticipated or prepared for. It took over an hour to reach the designated crossing point, during which time my anxiety continued building. When I finally made my first attempt, I immediately stepped hip-deep into thick mud and became thoroughly stuck. Fortunately, I had tightened my shoes in anticipation of muddy conditions, but the situation was far worse than expected. I struggled to extract myself on hands and knees without losing my shoes entirely.

After exploring alternative entry points, I decided to attempt the crossing again, this time committing fully to the process. I told myself I would swim if necessary, and that swimming might actually be easier than trying to wade through the mud. The water progressively got deeper and deeper, eventually reaching my chest. I kept going, trusting that it wouldn’t get worse. Fortunately, it didn’t, and I eventually reached the far side completely soaked and covered in mud, along with all my gear.

Only after arriving in Santa Fe and checking the online Rio Grande flow data did I realize I had crossed during peak flow conditions—the water was almost 3ft higher than the levels during previous days. The peak flow was probably directly attributable to the intense rainfall throughout the area during the previous night. Under normal conditions, the crossing would have been manageable. Under flood conditions, it felt genuinely hazardous and was probably borderline irresponsible to attempt.

After some intense bushwhacking to gain higher ground, I found the trail that led up to the canyon rim. At the top, I took a substantial break to eat breakfast and dry what gear I could in the morning sun.

The remainder of the route was relatively straightforward and followed portions of the historic Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, the 1,600-mile trade route that connected Mexico City with Santa Fe during the Spanish colonial period.

On the final gravel road leading into Santa Fe, I discovered three full Blue Moon beer bottles in an open cardboard box by the roadside. After 12 days of wilderness travel, finding beer felt like extraordinary trail magic. Sadly, I was only able to drink one bottle—my stomach couldn’t handle more.

I had hoped to reach the Santa Fe Plaza without needing a headlamp, but darkness fell before 8pm. I donned my headlamp for the final time as I made my way through the familiar streets toward downtown. As I approached the plaza, I could hear music and festivities associated with the annual Santa Fe Fiesta—a celebration that dates back to 1712, making it one of the oldest continuously celebrated festivals in the United States. The plaza was buzzing with people, music, food vendors, and celebration. After 12 days of almost complete solitude, the sensory overload was overwhelming but also profoundly moving.

I reached the exact spot where I had started 12 days earlier in 304:17:06 hours = 12 days 16 hours 17 minutes 6 seconds of continuous forward progress.

Reflections on the route

The NNML deserves recognition as one of America’s premier long-distance hiking challenges. Brett Tucker’s vision of a grand tour through northern New Mexico succeeds brilliantly in showcasing the region’s incredible diversity while demanding a high level of backcountry skills from those who attempt it.

This route is decidedly not for beginners. The combination of challenging terrain, navigation, limited water sources, and exposure to rapidly changing weather conditions requires extensive experience. Yet for those with the requisite experience and preparation, the NNML offers an unparalleled journey through some of the most spectacular and culturally significant landscape in the American Southwest. From ancient Pueblo ruins to Hispanic villages that have maintained their traditions for centuries, from alpine peaks to desert mesas, this route provides a comprehensive immersion in the Land of Enchantment.

Acknowledgements

This achievement would not have been possible without the groundwork laid by Brett Tucker in creating and refining this incredible route. The detailed mapsets, waypoints, and resource guides he provides are essential for anyone contemplating an NNML attempt. The route represents years of exploration and refinement, resulting in a journey that truly captures the essence of northern New Mexico.

Special appreciation goes to the local trail maintenance volunteers and organizations, whose ongoing work keeps many of the route’s trail sections in good condition.

Last but not least, special thanks to Ursina!

Full report with more pics and captions at https://www.christofteuscher.com/aagaa/report-500mi-self-supported-northern-new-mexico-loop-fkt